Want to know the oldest complete sentence ever written in alphabetic script? It’s about head lice.

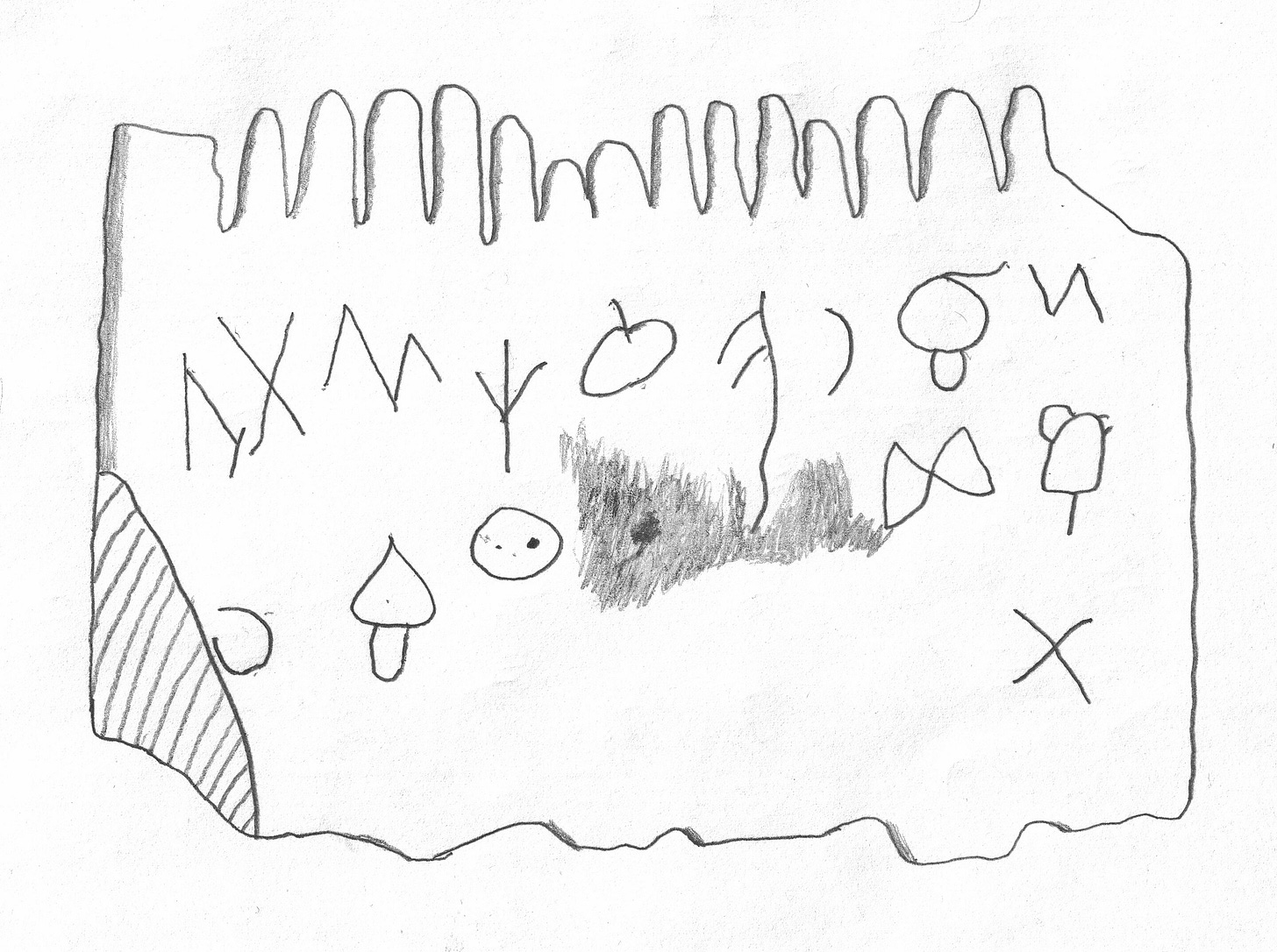

“May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.” Seven words scratched on a tiny ivory comb found at Tel Lachish in southern Israel.

Archaeologists pulled it from the ground in 2016, but nobody noticed the faint letters for five years. Madeleine Mumcuoglu was studying lice remains stuck in its teeth when she snapped a quick iPhone photo and zoomed in.

Not a royal decree. Not a religious text. Just someone desperate for relief from an itchy scalp, writing in Canaanite script 3,700 years ago. When you write in English today, you’re using a system invented by these ancient Canaanites who first matched letters to sounds.

Fourteen fine teeth on one side removed lice and eggs. Six wider teeth on the other untangled hair. Look familiar? Modern drugstore lice combs have the exact same design. Elephant ivory made this expensive, probably a gift. At just 3.5 centimeters across, you could hide it in your pocket. Did people feel embarrassed about head lice 3,700 years ago? Apparently yes.

When Combs Weren’t for Hair

Near Cambridge, England, archaeologists found something stranger. A two-inch comb carved from human skull bone, dating between 400 and 100 BCE.

Michael Marshall from the Museum of London Archaeology noticed the teeth showed zero wear marks. A drilled hole at the top meant someone wore this around their neck. Not a grooming tool at all. An amulet. Only two other bone combs exist in Britain, both within fifteen miles of Bar Hill.

Iron Age communities in Cambridgeshire carved combs from their dead. Maybe from important members whose presence they wanted to preserve. Your grandmother’s skull becomes an object of power you wear daily. That’s a very different relationship with ancestors than we have now.

The Revolution Nobody Noticed

Cooking tools don’t sound exciting until you realize they changed everything. Stone Age cutting tools from Ethiopia date back 2.6 million years, found at sites like Bokol Dora and Gona in the Afar region. First technology that let humans process meat their teeth couldn’t handle. Before that? Humans probably ate a lot of soft food and went hungry often.

Metates and manos show up at sites over 15,000 years old. Big flat stones with depressions worn into bedrock, used with hand-held grinding stones. Native Americans in Warner Valley, Oregon had permanent cooking stations where they pounded mesquite beans, seeds, and dried meat. Required serious arm strength.

Terra cotta pots revolutionized everything again. Romans used wide-mouthed bowls called olla or caccabus for basically everything. Charred food on the rim tells you what the last meal was. Carbonized residue shows recent cooking. Lipids absorbed into the clay preserve a longer history of every dish ever made in that pot.

Scientists analyzing scale buildup inside pots at Çatalhöyük in Turkey can now reconstruct Bronze Age diets. A cemetery in Xinjiang, China yielded pots with enough preserved material to show exactly what the Xiaohe people ate. Your cooking pot is basically a time capsule you don’t mean to create.

Copper cookware appeared around 9000 BCE. Mesopotamians perfected it by 4500 BCE, the first metal used on a large scale. Metal distributed heat better and lasted way longer than ceramic. Each innovation built on the last, driven by one question: how do we make food better?

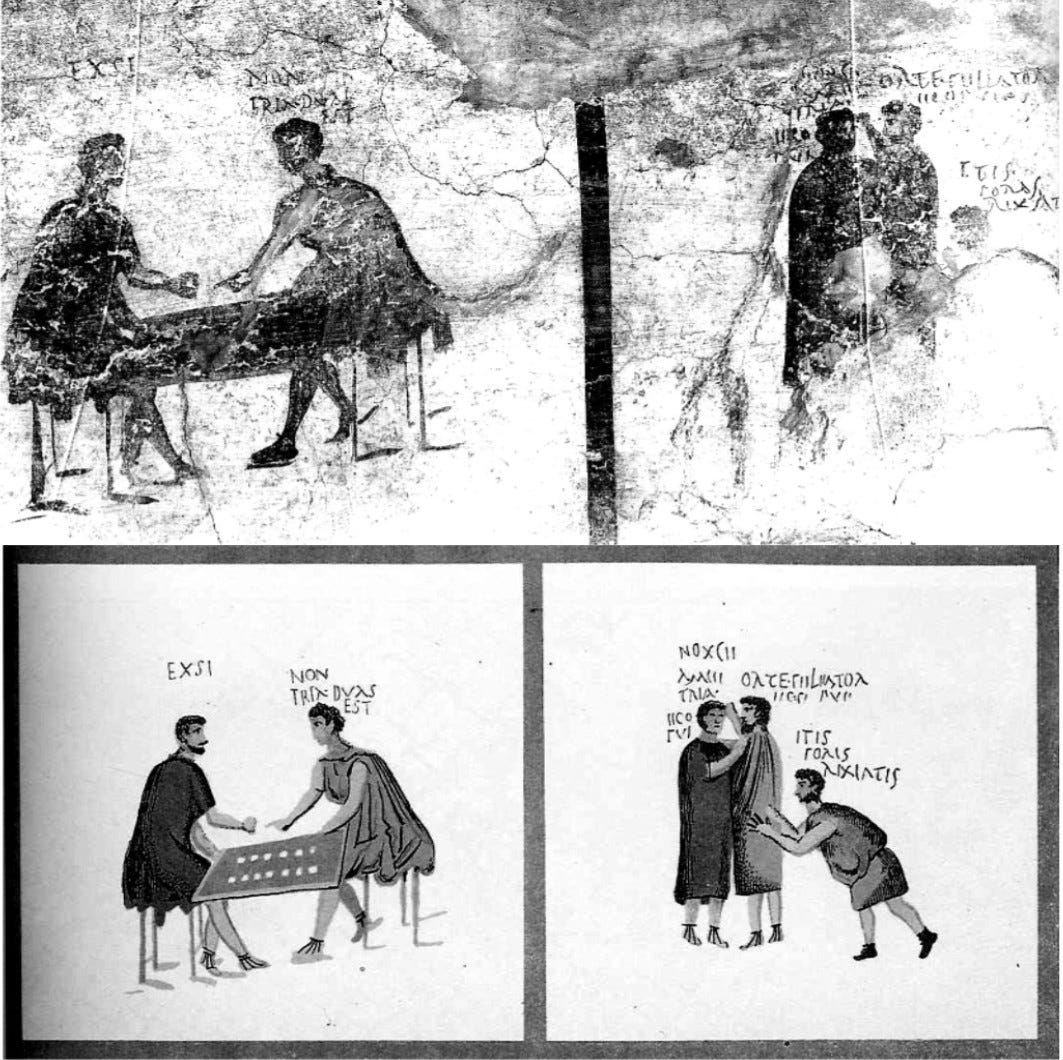

Dice and the Gods of Fortune

Why did Romans make such terrible dice? That’s the question archaeologists Jelmer Eerkens and Alex de Voogt wanted to answer. They studied 28 Roman dice from the Netherlands. Twenty-four were visibly lopsided.

Romans loved gambling. Gaming tables show up in homes, public spaces, ports. Professional gamblers carried loaded dice to Pompeii looking for drunk travelers. But here’s the weird part: 80 to 90 percent of all Roman dice were asymmetrical. Medieval dice? Only about half. Modern dice? Almost none.

Many Roman dice placed one and six on the larger opposing faces. On a lopsided die, numbers on bigger surfaces come up more often. Way more. Some Roman dice had a one in 2.4 chance of rolling certain numbers instead of one in six. Were they cheating?

Eerkens and de Voogt ran an experiment. They gave psychology students asymmetrical blank dice and asked them to add the dots. Students had no reason to cheat. Most put one and six on the largest faces anyway, especially when told opposing sides should sum to seven.

Production bias, not cheating. Students said it felt natural to start with the biggest face or save room for the six, which needs the most dots. Romans didn’t care if dice were perfect cubes. As long as it rolled, good enough.

But why didn’t they care? Ancient texts show Romans believed Fortuna, goddess of luck, controlled every throw. Probability theory didn’t exist for them. Cicero questioned whether gods determined dice rolls, showing some understanding, but his philosophy books reached almost nobody. Shape didn’t matter because they thought divine beings picked the outcome regardless.

Symmetrical dice became common only after probability theory spread, particularly through Blaise Pascal’s work in the 17th century. Mathematical thinking made dice makers care about precision.

What Got Thrown Away

Museums fill rooms with golden masks and jeweled crowns. Power and wealth on display. But a comb asking for lice relief tells you more about actual human life than any crown.

What did people eat for dinner? How did they deal with lice? Did they understand gambling odds? Broken everyday objects survived because nobody thought they were valuable enough to melt down. An ivory comb sat in storage for five years before anyone noticed writing on it. Bar Hill’s skull comb hid among 280,000 other artifacts.

Roll dice tonight and you’re connected to Romans who thought Fortuna controlled the outcome. Run a comb through your hair and you’re doing exactly what someone did 3,700 years ago while complaining about the same problem.

I’d love to get a translation of the argument they had.